For Fecal Transplants, Frozen Poop Just as Good

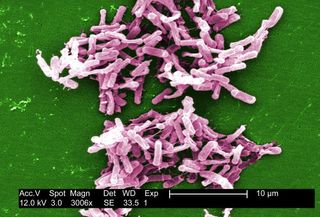

For people suffering with the intestine infection Clostridium difficile, the treatment sometimes referred to as a "poop transplant" may work just well with fresh or frozen fecal matter, researchers say.

In a new study, 10 patients with C. diff infections who received a transplant using frozen fecal material from healthy donors responded just as positively as the 10 patients treated with fresh fecal material, the researchers said. The procedure is intended to transplant beneficial microbes found in fecal matter.

Moreover, frozen fecal matter can make the operation easier on the patient. The use of fresh material requires patients to undergo a colonoscopy, whereas the frozen material can be delivered to a patient's digestive system via a tube that enters through the nose and reaches down to the stomach.

"For almost all patients in the study, this delivery was preferable to that by colonoscopy, which involves a preparatory 'cleaning out' of the colon, sedation or anesthesia, and is more costly," said study researcher Dr. Elizabeth Hohmann, of the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

As far as the esthetics of the procedure, or what she refers to as the "ick factor," Hohmann said that most patients overlooked it. Since C. diff infections can make people severely ill for a long time, patients focus more on getting better, she said. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

"When you have been sick for a year or more with diarrhea, and your quality of life has been greatly affected, you easily get past the ick factor," she told Live Science.

The research is published online today (April 24) in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the study, healthy adults who had undergone a comprehensive screening for infectious diseases donated stool samples. Donors were also asked to refrain from eating any common allergens, such as nuts or eggs, in the days before donation. The donated fecal matter was filtered, diluted, screened and frozen, then stored for at least four weeks to allow researchers to retest donors for any hidden infections.

The study's 20 patients included three children, and all participants had experienced three or more episodes of mild to moderate C. difficile infection, for which antibiotic treatment had failed, or they'd had two episodes serious enough to require hospitalization.

A single treatment cured 14 of the 20 participants, including eight in the fresh fecal matter group and six in the frozen group, a difference not considered significant in such a small study, the researchers said.

Among those whose infections were not cured, one participant declined additional treatment. The other five received a second treatment, which cured the infection in four patients, for an overall success rate of 90 percent, similar to that found in previous studies. Participants who received a second treatment were allowed to choose the route of administration; all chose to receive the frozen material through the stomach tube.

In the United States each year, C. difficile causes more than 250,000 infections requiring hospitalization, and 14,000 deaths.

For patients with recurrent or treatment-resistant infection, long-term treatment with antibiotics has had limited success, with symptoms recurring up to 30 percent of the time. Antibiotic treatment can often make matters worse, Hohmann said, by killing off beneficial, normal intestinal microbes that can keep such infections in check.

The research team also reported that since their pilot study of 20 patients, they have treating an additional 11 patients with frozen donor samples, and achieved a 91 percent success rate. Hohmann said the researchers are currently investigating an even more acceptable means of administration, via a capsule that would remain undigested until it reaches the small intestine.

"There aren't that many things in medicine that have a success rate of more than 90 percent," she said. "While this has yet to become a mainstream treatment, it is being considered more and more often."

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on LiveScience.