Iguana Relative Shows How Lizards Spread Worldwide

An 80-million-year-old lizard discovered in southern Brazil has provided a surprising clue about how these reptiles evolved, and where they once lived, according to a new study.

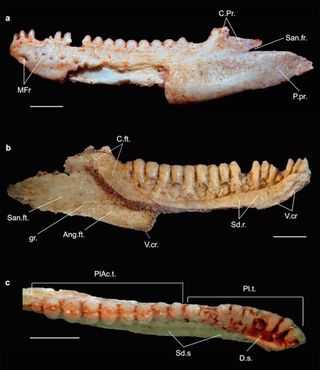

Until now, researchers had found acrodontans only in the Old World, including Africa and Asia. (This is a type of lizard is called an iguanian that has teeth fused to the top of its jaws, a group that includes chameleons and bearded dragons.) But the newfound fossil, a partial lower jaw of a new species of acrodontan, shows that they lived in the New World much earlier than thought.

The fossil suggests that acrodontans managed to distribute themselves worldwide before the ancient supercontinent Pangaea broke up about 200 million years ago, the researchers said. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

"This fossil is an 80-million-year-old specimen of an acrodontan in the New World," study co-author Michael Caldwell, a biological sciences professor at the University of Alberta in Canada, said in a statement. "It's a missing link in the sense of the paleobiogeography and possibly the origins of the group, so it's pretty good evidence to suggest that back in the lower part of the Cretaceous, the southern part of Pangaea was still a kind of single continental chunk."

Paleontologists discovered the fossil in the rock outcrops of desert that dates to the late Cretaceous in the Brazilian municipality of Cruzeiro do Oeste. The researchers named the new species Gueragama sulamericana — guera meaning "ancient" in native Brazilian; "agama" in reference to agamid, a family of iguanian lizards; and "sulamericana" meaning "from South America" in Portuguese.

The jaw is missing a few teeth, but has room for 18 of them, and the teeth almost uniformly increase in size from the front to the back of the mouth, the researchers found.

During the Late Cretaceous, G. sulamericana lived in an arid desert environment, although evidence of ancient wetlands suggests that water was available seasonably, the researchers said. G. sulamericana also had company. Other fossil findings, including "hundreds of bones" of the pterosaur species Caiuajara dobruskii, show that larger animals lived there, too, the researchers wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

G. sulamericana may have lived in burrows to avoid extreme daytime heat, just as some modern lizards do today, the researchers added.

Surprise finding

Among living lizards, iguanians comprise one of the most diverse groups, with more than 1,700 species. Previous research has found that acrodontan iguanians dominated the Old World, and nonacrodontan iguanians (such as iguanas) dominated the New World, particularly the American South, Caldwell said.

The oldest known acrodontans are from the early to middle Jurassic period in present-day India. However, now researchers know that acrodontans had spread elsewhere in the world by the late Cretaceous, the researchers said.

"This Gueragama sulamericana fossil indicates that the group is old, that it's probably southern Pangaean in its origin," Caldwell said. "After the [Pangaean] breakup, the acrodontans and chameleon group dominated in the Old World, and the iguanid side arose out of this acrodontan lineage that was left alone on South America."

Eventually, nonacrodontans replaced acrodontans in the Americas. But nonacrodontans remain as natives in the Old World, the researchers said.

"This is an Old World lizard in the New World at a time when we weren't expecting to find it," Caldwell said. "It answers a few questions about iguanid lizards and their origin."

The research was published online Aug. 26 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.