Photos: Blue Whales Swim Dangerously Close to Shipping Lanes

Blue Whale Movements

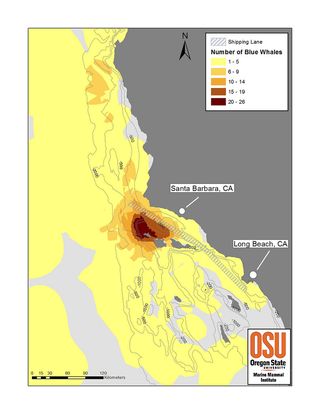

Researchers, reporting online July 23, 2014, in the journal PLOS ONE, have found that the feeding grounds of blue whales along the U.S. West Coast cross major shipping lanes. Shown here, a map of an area frequently used by tagged blue whales off southern California.

Spouting Whale

Extending more than 100 feet (33 meters) and weighing a whopping 330,000 pounds (150,000 kilograms), blue whales are Earth's largest animals. Perhaps luckily, they are gentle, grazing the oceans for little bits of food, which they capture in their gigantic mouths. Here, an aerial view of a spouting blue whale near a research boat.

Diving Whale

Researchers have been tracking these behemoths, attaching tags equipped with satellite transmitters to 171 blue whales (shown here a diving blue whale) off the coast of California between 1993 and 2008. The study is the most comprehensive look at the whales' movements ever undertaken.

Too Close for Comfort

After analyzing the paths of tagged blue whales within 200 miles (320 kilometers) of the U.S. West Coast, the researchers discovered the animals cross through busy shipping lanes off Los Angeles and San Francisco. In fact those shipping lanes overlap with the two areas of highest use by tagged blue whales off the U.S. West Coast during the summer and fall.

Shown here, a blue whale near the shipping channel off southern California.

Dead Blue Whale

The research findings could help save blue whales from ship strikes, such as this one – Oregon State University researchers examine a dead blue whale killed by a ship strike. In fact, the study scientists suggest shipping lanes be moved during the summer and fall when the whales are most abundant.

Whale-Ship Collision

Here, a blue whale killed by a ship strike in 2007 near Santa Barbara, California, next to Oregon State University's 85-foot research vessel called Pacific Storm.

Examining a whale

Oregon State University researchers examine a dead blue whale killed by a ship strike.

The study researchers say it is in the best interests of both the whales and shipping companies to avoid whale strikes. "When ships hit whales, the shipping companies' insurance companies require them to have their ships inspected for damage before they go across the ocean," said lead study author Ladd Irvine, a marine mammal ecologist at Oregon State University. "There are limited facilities to do that, and ships have to sit for a long time and miss out on income while they get inspected."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.