Extinct Hippolike Creature Was Prehistoric Vacuum Cleaner

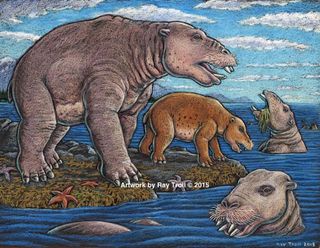

About 23 million years ago, an ancient hippo-size mammal used its long snout like a vacuum cleaner, suctioning up food from the heavily vegetated shoreline whenever it was hungry, a new study finds.

Fossils of the newfound species — found on the Aleutian Islands' Unalaska, the location of the popular reality TV show "Deadliest Catch" — show that it had a long snout and tusks. Its unique tooth and jaw structure indicates it was a vegetarian, said study co-author Louis Jacobs, a vertebrate paleontologist at Southern Methodist University in Texas.

"They were marine mammals, but they were not completely marine, like whales," Jacobs said in a video about his research. It's likely they lived both on land and in water, like seals, and could move around on land like a "big, lumbering, clumsy sort of giant sloth," he said. [The 12 Weirdest Animal Discoveries]

"But when they were in the water, they swam like polar bears," Jacobs said. "They were front-limb-powered swimmers."

Researchers named the new species Ounalashkastylus tomidai. The word Ounalashka translates to "near the peninsula" in the Aleut language of the indigenous Aleutian Island people, and stylus is Latin for "column," a reference to the creatures' column-shaped teeth. The species name tomidai honors the Japanese vertebrate paleontologist Yukimitsu Tomida.

O. tomidai belongs to the order Desmostylia — the only known order of marine mammals to go completely extinct, the researchers said. Desmostylians lived between about 33 million and 10 million years ago along the coastline of the North Pacific Ocean, and the new specimens show that the order was more diverse than previously thought, said co-researcher Anthony Fiorillo, chief curator at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Texas.

The creature's odd, columnar teeth and suction-style feeding have never been seen in any other mammal, the researchers said. When O. tomidai ate, it would have buttressed its lower jaw and teeth against the upper jaw, and then used its powerful muscles to slurp up vegetation — such as marine algae, sea grass and other near-shore plants — from the coastal area, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The new animal — when compared to one of a different species from Japan — made us realize that Desmos [Desmostylians] do not chew like any other animal," Jacobs said in a statement. "They clench their teeth, root up plants and suck them in."

"No other mammal eats like that," he added. "The enamel rings on the teeth show wear and polish, but they don't reveal consistent patterns related to habitual chewing motions."

The fossils represent four O. tomidai, including one baby, the researchers said.

"The baby tells us they had a breeding population up there," Jacobs said. "They must have stayed in sheltered areas to protect the young from surf and currents."

So, what would a group of O. tomidai be called? Rather than a pack, herd or gaggle, for example, they decided on a "troll," in honor of the Alaskan artist Ray Troll, who frequently illustrates Desmostylia animals.

Want to see images of the new findings? You can download 3D renderings of the fossils. The study was published online Oct. 1 in the journal Historical Biology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular