Mountainous Fib: Andes Lie About Their Age

The Andes are the world's second greatest mountain region and new research suggests that at least one portion of that region has been lying about its age.

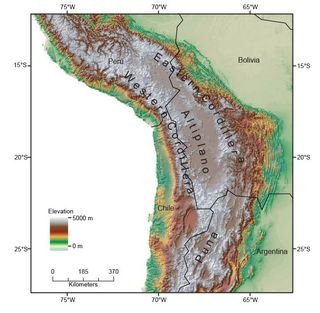

For years, the evidence has been piling up that the Central Andes surged into being about 10 million years ago -- a very short time ago geologically speaking. Now new evidence from volcanic materials on the Puna Plateau suggests that the area was already 4 kilometers high as far back as 36 million years ago. If so, it sets the area apart from the Altiplano, to the north, which is lower and younger, and adds yet another twist to the puzzling processes that created the range.

Photos: World's Largest Salt Flat

Team of researchers ventured to the very remote Puna Plateau in Argentina and collected volcanic ash samples that they could study in the lab to determine not only how long ago the ash was erupted from volcanoes, but how far above sea level.

The age was determined by studying the ratios of uranium and lead in tiny zircons crystals. These two elements serve as an internal radiometric timekeepers for volcanic rocks, since uranium decays into lead at well-known rates over millions of years.

Next, the researchers looked for the elevation clues in bits of volcanic glass, or obsidian, that formed in the ash.

“The little glass shards cool and take on water from the environment,” explained Robin Canavan, a PhD candidate at Yale University and the lead author on a paper about the work in the March 31 issue of the journal Geology.

Photos: The World's 'Eight-Thousander' Mountains

It's the water that reveals the elevation, because as moist air moves up mountains and the water rains (or snows) out, the air tends to lose the heavier kinds of water first -- those made from heavy hydrogen and heavy oxygen isotopes. The effect can be seen today in surface waters in mountains around the world: lighter isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen in H2O are more enriched at higher elevations. Those same isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen can be found captured in volcanic glass.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By putting the radiometic dating together with the paleo-elevation information from the volcanic glass, the team could determine what height the Puna Plateau was when the volcanic ash was deposited on the ground.

“Our work suggests that the region south of the Central Andean plateau, the southern half the Puna, has had a surface elevation very close to modern 4 kilometers (13,000 feet) for 36 million years,” Canavan said. “This pushes it pretty far back from what previous work suggested.”

The discovery is especially appreciated by geologists studying the nearby Altiplano, which appears to have a very different history.

“The Puna and other Altiplano look similar, but they have different mechanisms,” said Carmala Garzione, professor and chair of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Rochester. “There are fundamentally different processes that are leading to the uplift.”

Photos: Stunning Auroras Seen Over Swedish Mountains

Both are part of the uplift caused by the subduction of ocean crust under the South American continent. But there are other things going on to thicken the crust and cause the mountains to buoy especially high in the Andes compared to other subduction zones.

The Altiplano, for instance, has a large, high basin. Whereas the Puna has several smaller basins. This, to Garzione, suggests that the Puna has been shortened, or squeezed, which could play a role in its earlier high elevation.

“The next step will be to get more geophysical data to get more information at depth,” said Garzione. Seismic data could help show the structures inside and under the mountains to explain the history even better. There is historic seismic data from the 1990s that is being reprocessed by other researchers to learn more about the subsurface, she said.

This story was provided by Discovery News.

Most Popular