NASA Satellite Captures Amazing 3D Videos of Rain, Snow

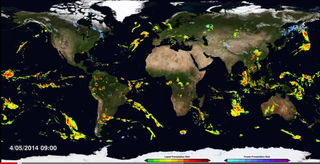

Mesmerizing and swirling animations of rain and snow dance across a map of the Earth, shown in a video released yesterday (Feb. 26) by NASA's Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission.

The NASA video captures worldwide precipitation from April to September 2014, and even shows Hurricane Arthur twist into a tropical storm from July 2 to 4 in the Atlantic Ocean, said Gail Skofronick-Jackson, a GPM project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The "GPM mission is the first coordinated international satellite network that provides near real-time global estimates of rain and snow," Skofronick-Jackson said at news conference yesterday. [Weirdo Weather: 7 Rare Weather Events]

The video is the product of the GPM Core Observatory, launched one year ago on Feb. 27 by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. Like an orchestra conductor, the observatory unifies precipitation measurements from a network of 12 international satellites, combining them into a harmonious product called IMERG, or Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM. IMERG can assemble the data into one near-universal map, NASA researchers said.

IMERG provides global precipitation rates every 30 minutes, and has a 5- by 5-mile (8- by 8-kilometer) resolution, creating an unprecedented view of rain and snow affecting cities and suburbs, Skofronick-Jackson said.

The new video shows a detailed view of precipitation levels around the world, from 60 degrees north to 60 degrees south latitude, or from the Northwest Territories in Canada to below the southern tip of Argentina,researchers said.

"In this imagery, you can see the deep tropical convective storms popping up along the equator," Skofronick-Jackson said. "These evaporate heat from the ocean's surface and transport it high into the atmosphere for redistribution in the Earth's system."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

She added, "Along the mid-latitudes, you can see the large frontal systems that persist for days, moving water and heat across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Snow, shown in blue, is found in the Southern Hemisphere, where it is winter during this imagery."

IMERG data is accessible to both the public and researchers within about four hours of a precipitation event, and may help emergency officials predict the locations of cyclones, floods and landslides, Skofronick-Jackson said.

GPM has a number of other advanced instruments. NASA equipment on the network of satellites can take an X-ray-like image of precipitation intensity, which can show the internal characteristics of clouds and precipitation, she said. And "the radar, from Japan, takes three-dimensional imagery of precipitation, almost like a CT scan like your doctor would do," Skofronick-Jackson said.

For instance, a 3D video from the GPM Core Observatory captured a snowstorm that left 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm) of snow over areas of Kentucky, West Virginia and North Carolina on Feb. 17, NASA researchers said.

The GPM Core Observatory is one of five missions that NASA has added to its orbiting Earth-observing fleet this past year, the largest number of NASA launches in more than 10 years, researchers said. The other missions include the Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP), NASA's Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 satellite, RapidScat (which measures oceanic winds) and the Cloud-Aerosol Transport System (CATS) that is now attached to the International Space Station.

All of these instruments will help scientists and the public to understand how carbon dioxide, rain and snowfall, ocean winds and aerosol particles act on a global scale, NASA researchers said. The new data may also help researchers understand and predict short-term weather and long-term climate, they said.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.